CANADIAN LITERATURE: revolushun in the t.dot: reviewing d’bi young and Motion

Reviewed by T.L. Cowan

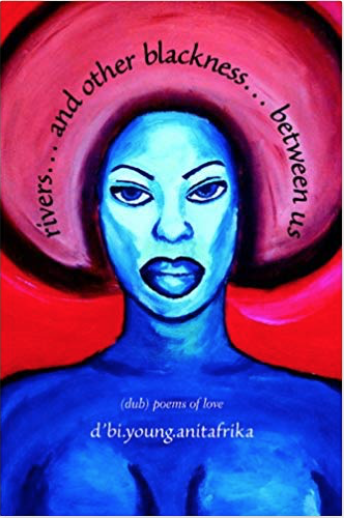

The two recent publications from Women’s Press reviewed here come from two of Toronto’s most popular and respected-and dynamic-performance poets: d’bi.young.anitafrika and Motion. Both collections refreshingly move beyond the transcription model of books by performance poets, showing equal attention to the look and sound of their poetries, but they are very different books.

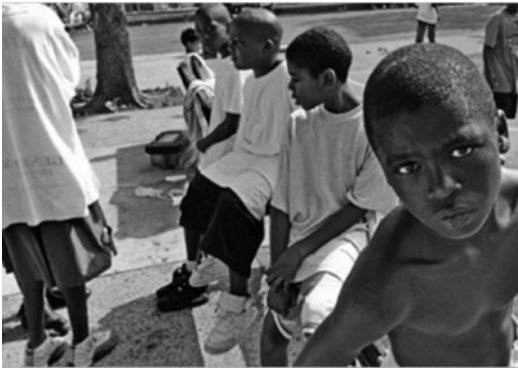

In the preface to her first collection, art on black, d’bi.young.anitafrika defines dub as follows: “dub is word. dub is sound. dub is powah. dub poetry is performance / poetry / politrix / roots / reggae” and identifies four elements of dub poetry-language, musicality, political content, and performance. Since then, anitafrika has elaborated three additional elements-urgency, sacredness, and integrity-which infuse and inform her own practice of dub. These additional elements signal the arrival of the visionary poetics found in rivers… and other blackness… between us, a book that confronts systemic racism in Toronto, the ongoing global effects of colonialism and imperialism, and pursues a vision of a just future. In “young black,” anitafrika repeats the incantation “you are brilliant and beautiful and / strong and rare” in a poem in which puns play alongside explicit commentary on local, national, and global politics:

In the preface to her first collection, art on black, d’bi.young.anitafrika defines dub as follows: “dub is word. dub is sound. dub is powah. dub poetry is performance / poetry / politrix / roots / reggae” and identifies four elements of dub poetry-language, musicality, political content, and performance. Since then, anitafrika has elaborated three additional elements-urgency, sacredness, and integrity-which infuse and inform her own practice of dub. These additional elements signal the arrival of the visionary poetics found in rivers… and other blackness… between us, a book that confronts systemic racism in Toronto, the ongoing global effects of colonialism and imperialism, and pursues a vision of a just future. In “young black,” anitafrika repeats the incantation “you are brilliant and beautiful and / strong and rare” in a poem in which puns play alongside explicit commentary on local, national, and global politics:

because I am more than the roundness of my ass

the width of my tits

the thickness of my thighs

the depth of my hips

the glimmity-glammity hold him tight

all through the night

is not necessarily my numbah-one priority

. . .

we

walking through metal detectors in school

that refuse to detect the rape and pillage

recolonized by the great

harris-tocracy

we

experiencing

the military’s militarization

of high school and middle school education

police officers turned hall monitors.

Following in the dub tradition, anitafrika makes explicit her commitment to “revolushun.” And more than even a political revolution, it is a “revolushun” in poetic language and form. Throughout the book, anitafrika switches between Creole and official “Standard English,” and enacts dub’s unofficial, emphatic intervention into this official world and its language. For the most part, anitafrika opts for a direct treatment of her subject; her poems operate primarily in the realm of what performance scholar Rebecca Schneider calls “explosive literality.” At points, however, she ventures into more fragmentary and dramatic forms as in “when the love is not enough: the conversation i never had with billie holiday,” a mournful love song in two voices, a dialogue that reflects anitafrika’s skill as a playwright.

Overall, the poems in rivers embody anitafrika’s seven elements of dub. Some readers may resist these elements and balk at the polemical tone of the book as a whole, but I encourage readers to consider these elements, and the poems they produce, in the context of our contemporary moment, in the context of the city section of the morning newspaper, and to reflect how this poet, and others working in the dub tradition, refuse to hide behind a veil of obscurity, and resist oppression with words, insisting that these words can do something more than sit on a page.

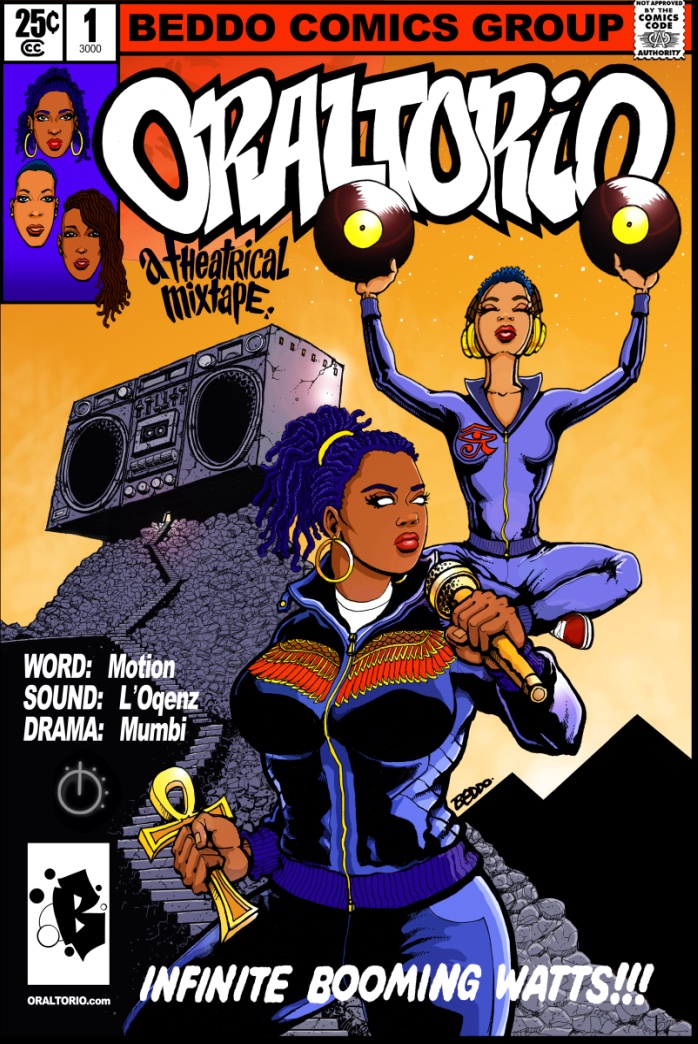

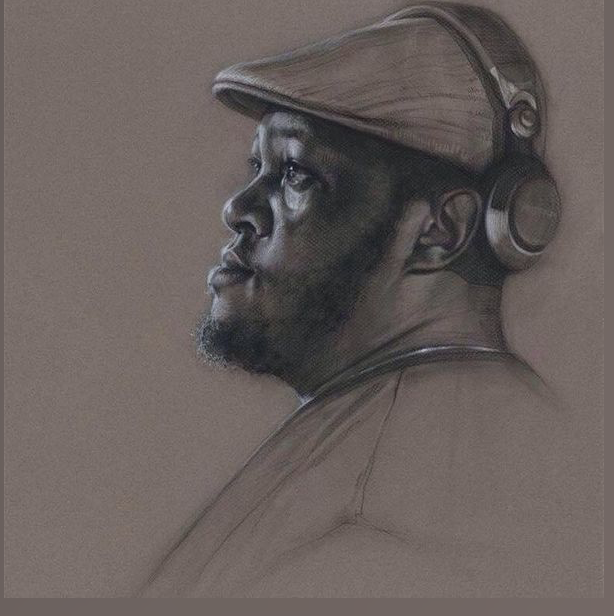

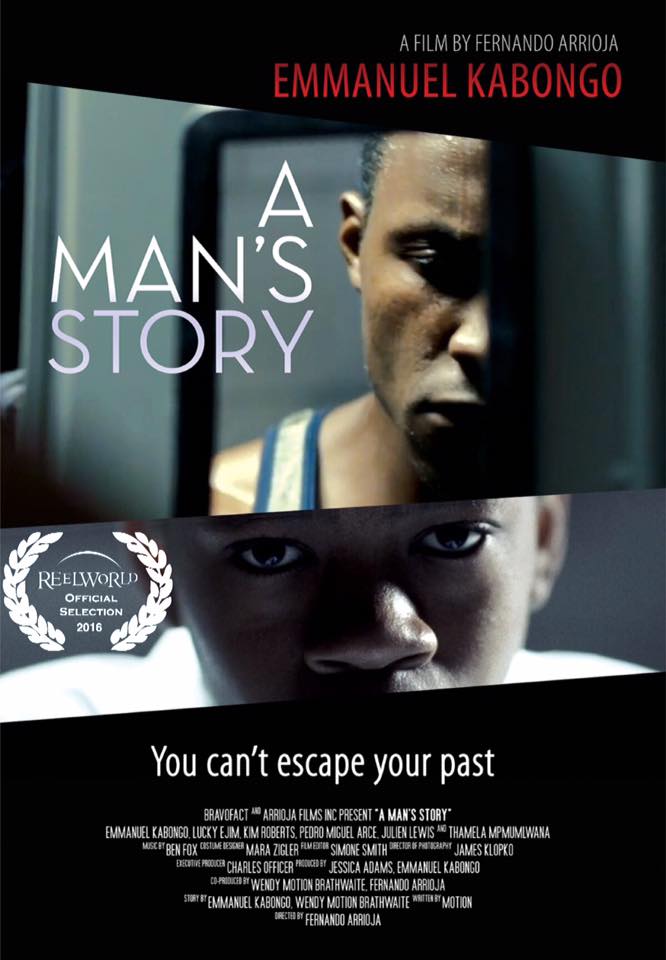

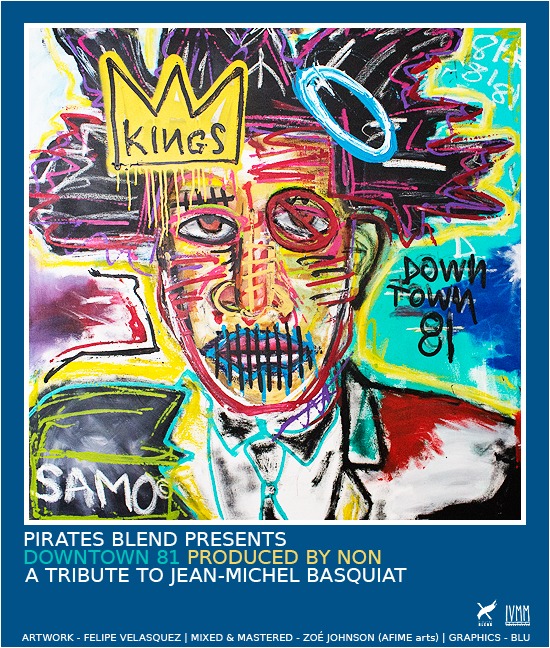

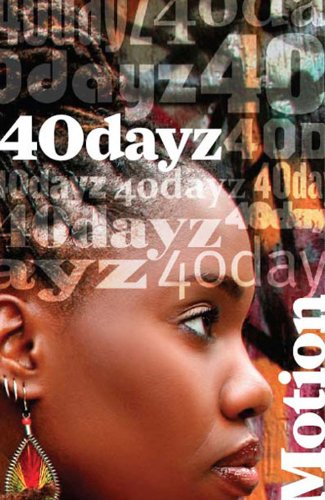

While anitafrika’s poems read as the verbal weapons of a pacifist street-fighter, Motion’s new collection, 40 dayz, is an urban, funk anthem for the T.Dot-Toronto in 2008. These poems focus mainly on a series of vignettes about life in Toronto’s North End and are figured through a series of metaphors that at once embrace and reject, reflect and conceal their own trajectories. Unlike the straightforward, linear narratives of much of the popular spoken word of today, Motion’s poems-which several times reminded me of the work of New York slammer-turned-sound-poet, Tracie Morris-mostly avoid the didactic approach in favour of vivid, image-based, but still political, long lyrics. While there is restraint here, I appreciate the revelations as well, and the irrepressibility and emergence that, for me, bring life to these poems. For example, “woman,” a poem that reveals the torment of watching a friend undergo cancer treatment, lays bare the painful ritual of hospital visits:

While anitafrika’s poems read as the verbal weapons of a pacifist street-fighter, Motion’s new collection, 40 dayz, is an urban, funk anthem for the T.Dot-Toronto in 2008. These poems focus mainly on a series of vignettes about life in Toronto’s North End and are figured through a series of metaphors that at once embrace and reject, reflect and conceal their own trajectories. Unlike the straightforward, linear narratives of much of the popular spoken word of today, Motion’s poems-which several times reminded me of the work of New York slammer-turned-sound-poet, Tracie Morris-mostly avoid the didactic approach in favour of vivid, image-based, but still political, long lyrics. While there is restraint here, I appreciate the revelations as well, and the irrepressibility and emergence that, for me, bring life to these poems. For example, “woman,” a poem that reveals the torment of watching a friend undergo cancer treatment, lays bare the painful ritual of hospital visits:

when we’d say goodbye

it was just till tomorrow

another day of chat chatting

bawl bawling

another 24 hour crisis

a next episode of girl I got your back.

Similarly, and this is a passage that particularly made me think of Morris, ” the calling” writes the heat of a summer night in Toronto along with a set of contradictions for which the poet has no solution:

buckles bones rip knots from limbs

lost and seeking

hearing home in a clearing

of dust

dancers jeaned skirted

sneakered and sandalled

sweaty and silent speak

and cry as bodies wild out

wrenching against chains

leaping from ship boards

beating down kicking.

The only question marks on my copy of this book occur beside images that were, a few times, abstract to the point of disguise, and I couldn’t figure out what the poet was hiding, or why she was hiding it. However, taken as a whole, this book brings the reader on a sometimes boisterous, sometimes contemplative bus ride across an urban wilderness, through Toronto, to Kingston’s jails, and to South Africa. 40 dayz is a New Testament of Toronto poetry.

Finally, there is one similarity between these books that I want to draw attention to here. Both poets give significant weight to “womb” language and imagery, and both draw a generative power from what anitafrika calls a “wombanist” approach to poetry and politics. For some, this “wombanism” may cause a gender-essentialist alarm to sound, and certainly this is my first reaction. My Third-Waver feminist politics tell me that the danger of this “wombanism” is that it risks universalizing women via biology. But I wonder, too, if, as Motion’s section title “transformashun” implies, these books mark a shift both in contemporary poetics and politics. Is it possible that we are in a post-anti-essentialist moment, and that these collections respond to the anxieties of dealing with the materiality of gender, especially the ways that these anxieties manifest in white feminism? This is a question that these collections refuse to answer, but I hope that it is one that others will ask too.